Hey,

As an editor and someone who’s been teaching creative writing and narrative theory for about a decade, I get asked a lot of questions about the process of writing. I do not presume to have the answers, of course, but I am a natural pattern-spotter, and when the same questions come up again and again, I get to wondering about why that might be. Which leads to a deep dive of thinking, researching, pondering, musing, and other synonyms.

After this process, I still may not have an answer, but I do end up with plenty of ideas (and usually even more questions).

So I thought it might be useful to share some of these, given that we all seem to come across the same sticking points, pitfalls and sheer bafflement when it comes to writing. (I might even make it a monthly series — so if you have any questions you’d like me to consider/ponder/deliberate over, then please gimme a shout.)

And thus, without further waffle, let’s get into my very first deep dive Q&A.

QUESTION: Is My Writing Derivative?

Over the past month or so, I’ve had several completely unrelated conversations with writers concerned about whether their work is somehow ‘derivative’. First off, I hate that word — or, rather, how it is usually interpreted — because all it really means is that something is a product of something else.

Of course, it’s most commonly used to denigrate a piece of work, by implying that it’s unoriginal, a ripoff, or some lazy attempt to recreate an existing piece of work.

By definition, this would apply to around 90% of Shakespeare’s work, which was cribbed (sometimes wholesale) from Plutarch, Ovid, Holinshed’s Chronicals, Philip Sidney, and a buttload of others — even his own contemporaries, whose work he re-worked and adapted at will (pun 100% intended).

Because that’s how stories get passed on. It’s also how we honour stories, apply them to new circumstances and learn from them. It’s how we keep warning humanity of the mistakes we’ve been making for hundreds of years, and rejoice in the fact that humans have also been falling in love and making fart jokes for all that time.

So, in its loosest sense, ‘derivative’ can simply mean inspired by something else. Or inspired by many things.

Derivative can also refer to something that’s been intentionally adapted, expanded, or overtly based on another piece of work. (Psst. See my previous post about the latest works entering the public domain for some delightful irony.)

It doesn’t have to be an insult, and it doesn’t have to mean ‘lesser’.

And there’s really no need for any writer to be afraid of being ‘unoriginal’ (look, this post is going to have a lot of inverted commas, ok?).

Example 1:

I’m currently working with an author who is writing a fantastical romp of an adventure story. The moment I read her outline I said, “Oh heck yes, I would love to read this — it sounds like a cross between [popular film] and [popular video game]. Two of my absolute favourites!”

This writer was pretty delighted to hear that, because they were her favourites, too, which is exactly why she wanted to write this kind of story.

Of course, it’s not a carbon copy of either of those influences. Sure, it’s set in a similar time period, and contains a similar vibe of fast-paced action and wise-cracking characters, but it’s also got its own unique fictional universe with its own unique plot and subplots and protagonists and a million different differences.

So, is it derivative?

Example 2:

I’m also currently working with another author who stated his influences right from the get-go: three very famous writers with distinctive voices, all working within a particular genre. They are some of his favourite authors (mine too!), and he said he deliberately set out to write something with a similar tone and style.

Reader, he nails it. But not in a way that feels like he’s trying to copy, or even directly emulate them. Again, it’s more of a VIBE. Something you can’t even quite put your finger on. But there’s a real sense of warm familiarity as you read it — a literal embodiment of ‘if you liked these guys, then you’ll like this.’ But even if I hadn’t already been familiar with his influences, it would still be just as joyful, because it was born from a place of appreciation. He’s taken what makes those influences enjoyable (wit, asburdism, and unexpected philosphical insights), and used them to bring his own story to life.

And yet. When I asked if he had any specific areas of concern or questions before I began reviewing his work, he said: “Is what I’m writing derivative, or glorified fanfiction?”

Well, is it?

Example 3:

I recently met up with one of my loveliest writer friends, with whom I share a deep, dark secret. A ‘forbidden pleasure’. We met through a mutual love of Shakespeare and films and video games, and quickly discovered that we both also write fanfiction. Gasp, the secret is out! The shame! The horror! Ehhh, yeah, whatever.

Because what is fanfiction but an expansion of an existing fictional world? Christopher Marlowe’s Jew of Malta walked so that Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice could run. Hamlet is not Shakespeare’s original creation, but a reworking of centuries-old revenge plays with the same(ish) storyline. The Star Wars Expanded Universe came to life with the explicit aim of creating new (derivative) content for hungry fans, and fill out George Lucas’ (patchy as hell) worldbuilding. And what of the Marvel Cinematic Universe? How many Spidermen (Spidermans?) have there ever been — on paper, in animation, on screen, in games? (A lot.)

My friend and I use fanfiction to continue to spend time in the fictional worlds we love, and explore facets of those characters and stories that may not have been in the original work. My friend plays with alternate universes (AUs) — transposing her favourite characters into different timeframes, settings and circumstances. I like to fill in backstories and moments that might be skipped over in canon. We’re kids with little toy figures. We’re playing dress-up and acting out our favourite cartoons in the playground. We’re having fun.

And yet, we both rarely admit to writing fanfic to others. Why? Because to those who don’t actually read it, it’s generally seen as trashy derivative work at best, and dodgy erotica at worst.

(Fun fact #1: a lot of fanfiction is perfectly PG rated, thank you very much, and may not even involve anything romance-related.)

(Fun fact #2: the generalised snooty attitude to romance and erotica is steeped in a particular kind of patriarchal bullshit based on a fundamental discomfort with the existence of genres written predominantly by women concerning such societally dangerous matters as sexual liberation… But that’s a whole other article, and I digress.)

Look. Some of the most impactful writing I’ve ever read was posted anonymously on a fanfiction website. And some of the worst writing I’ve ever read was published traditionally.

Look. One method of making it in the TV screenwriting world is to write spec scripts based on existing series, as proof that you can embody a certain character or storyworld accurately; to show you can work to a pre-determined set of parameters; and to build your portfolio across a range of genres and styles. Sounds a lot like fanfiction to me.

Look. My friend wrote her first novel-length work as an AU fanfic. Her readers love it so much they’ve created fan-artwork of her original characters. One of them even had a beautifully bound book version printed and sent it to her. What author wouldn’t dream of that kind of recognition?

For new writers, fanfiction can offer a readymade sandbox to play in and develop their skills without pressure. They’re free to experiment with plot and characterisation within a familiar space, fuelled by the love of the story.

And will you look at that — something we keep coming back to in each of these examples — the love of the story.

Almost as if we’re supposed to enjoy writing or something. Hmm.

So what is so freaking bad about derivative writing?

That, indeed, is the question.

I could go deeper into certain cultural, class-based attitudes towards literature.

I could talk more about why certain genres are often considered lesser than others.

I could even discuss the oxymoronic attitude that ‘popular’ fiction is somehow not as important as niche, often inaccessible work.

I could definitely wax lyrical about how self-published books can — and do — perform much better than traditionally-published ones, and are often written by authors who would otherwise be systemically excluded from the literary industry.

I could suggest that anyone criticising other people’s work for being derivative simply because their influences are showing, might want to examine their own biases first.

But that, again, is a whole other article.

Instead, I will remind you that we are all the (derivative) product of our influences. Every story that was told to us from birth. Every story we consumed under the bedcovers with a torch, long after bedtime. Every story we watched and re-watched with square eyes. Every comic book, audio book, song, play, comedy sketch, documentary and panto. Even the stories we hated. Especially the ones we thought we could do better.

We are the product of myriad influences, and that is frankly glorious.

Because even if you lined up a hundred writers and fed them the same hundred stories as source material, they would still come up with something unique, because they would each be bringing their own unique experiences and perspectives to the process of creation.

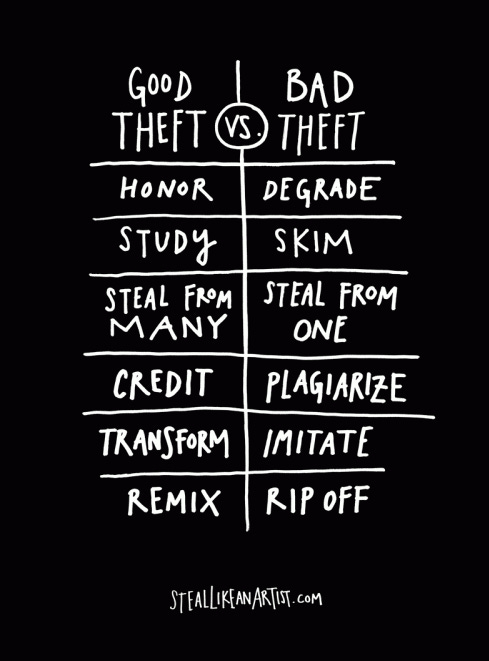

Obviously I’m not saying we should brazenly steal, plaigiarise and replicate other works with wild abandon — there are copyright laws for good reason — and there are many good ways to ‘steal like an artist’ in order to transform your inspirations into something uniquely yours:

But look. Popular fiction, by its definition, means that it is enjoyed by many people. Those people may have very different backgrounds and lives and opinions, but there’s something in the story that unites them in their humanity.

And the reason a story becomes popular is often because it was derived from something similar, something familiar, something equally popular; a seed of an idea or a theme or style or journey or challenge that has — for eons — resonated with audiences.

Embracing those influences can even make you a better writer. I want to make people feel like this book made me feel. I want to make people laugh like this author does. I want to learn how to be as sparse and succinct as this particular writing style. I want to combine this and that and all of these things in a big melting pot.

Springboarding off your influences isn’t derivative — it's expansive. It's a love letter to what speaks to you as a writer; a love-letter to other readers who enjoy the same kind of stories as you do.

Because that is the shared power of fiction. The hand-me-down stories around the campfire. The tale that gets altered slightly with every telling, until it’s something brand new. We write stories about worlds we want to live in, characters we want to be, dangers we want to avoid, happiness we want to find. We write to understsand ourselves, and others, and people, and life, the universe and everything.

And as it turns out, we never seem to get tired of those stories, do we?

Wow, this was a big one. If you’ve made it this far, thank you for reading, and I would love to know all about your own influences, so please leave me a comment or a reply.

Oh, and if you have a writing/editing-related question you’d like to submit for the next Q&A Deep Dive then lemme know! There could be an impassioned rant with your name on very soon.

I love this Jo, and I can't count the amount of times I've not-written because I thought my idea/character/premise wasn't original enough. I wish I could send this back in time to my 20 year-old self.